Medetomidine

Last updated December 2025

Medetomidine is a veterinary sedative, similar to xylazine (tranq), that was first found in Philadelphia’s drug supply in May 2024. Medetomidine is 100-200 times more potent than xylazine and can cause longer-lasting sedation, low heart rates, and more severe withdrawal symptoms. It is not an opioid but is found in the dope (street opioid) supply.

Medetomidine is replacing xylazine in the city’s drug supply. Since the introduction of medetomidine, there has been an increase in the variation and severity of withdrawal symptoms, a decrease in the number of patients seeking treatment for xylazine-associated wounds, and a decrease in the presence of xylazine in Philadelphia’s drug supply. From May 2024 to November 2024, the percentage of Philadelphia dope samples with medetomidine increased from 29% to 87%, while the percentage of samples with xylazine decreased from 97% to 42%, suggesting that medetomidine is quickly overtaking xylazine in the dope supply. During this period, medetomidine was also found in overdose death data from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health’s (PDPH) Medical Examiner’s Office (MEO) and, like xylazine, was always found in combination with fentanyl.

Medetomidine symptoms and overdose

The main effect of medetomidine is heavy sedation, but it can also cause low blood pressure and slow heart rate, dizziness, extreme tiredness, shortness of breath, nausea, blurred vision, and confusion.

Because of the heavy sedation, someone who overdosed from a drug containing medetomidine may stay sedated and non-responsive after receiving naloxone, even if the overdose is successfully reversed. That is because medetomidine is not an opioid, so the sedation from medetomidine will not be reversed by using naloxone. So, when you are reversing an overdose, it is important to focus on the person breathing rather than responsiveness. This means ensuring that the person takes at least one breath every five seconds and is not pale, gray, or blue. If possible, monitor the person until they become responsive, or transition them to EMS or a bystander.

Visit our training page to learn how to recognize and reverse an opioid overdose.

Visit our get supplies page to get medetomidine test strips.

Medetomidine withdrawal

The effects of medetomidine differ from xylazine. This is clearly displayed in new emergency department (ED) syndromic data, which shows a rapid increase in ED visits for substance use withdrawal and a rapid decrease in ED visits for substance use related skin and soft tissue infections following the introduction of medetomidine. Read more about these trends in our May 2025 CHART.

Medetomidine withdrawal has been described in PDPH’s December 2024 HAN and two MMRW reports from the CDC. The symptoms of medetomidine withdrawal can start rapidly and include:

Fast heart rate (>100 beats per minute)

Dangerously high blood pressure (>180/100)

Uncontrollable nausea and vomiting

Tremor

Excessive sweating

Changing levels of alertness

Most patients who go to the hospital for medetomidine withdrawal need to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Treatment strategies for medetomidine withdrawal are evolving, and are described in PDPH’s December HAN, as well as the University of Pennsylvania Center for Addiction Medicine and Policy website.

PDPH recommends a lower threshold in outpatient settings to refer patients experiencing withdrawal to a higher level of care if they are exhibiting severe symptoms.

Fast facts

-

Yes. Medetomidine test strips are now commercially available. These test strips allow individuals to test for the presence or absence of medetomidine in their substances. The Philadelphia Department of Public Health works with local community groups to distribute the tests strips. Find a community partner on the get supplies page. Medetomidine test strips work like fentanyl test strips- you just need to dip the strip in a mixture of a small amount of drug residue and water. Reading the results is the same as reading a fentanyl test strip, two lines mean that it is negative and medetomidine hasn't been detected, and one line means positive and that medetomidine was detected.

Medetomidine test strips are a new tool. Information on the effects of the drug and recommendations for the use of these test strips can change. Continue to check this page for updated information.

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health will continue to work with a forensic toxicology lab to test drug samples and identify emerging drugs, including medetomidine.

-

Unfortunately, medetomidine has been found in almost 90% of dope drug samples. However, if you're not sure, you can follow these steps.

First, try to ask around and see how the drug is making other people feel before you buy or use it. Since medetomidine can cause a really heavy nod, try to use somewhere that you will be safe and won’t fall and hurt yourself. Finally, if you think there is medetomidine in your dope let others know - including someone at your local exchange program - so folks know to be careful.

-

No, other states including North Carolina, Ohio, and Illinois have identified medetomidine in their local supply. Read more about their cases in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

-

Not exactly. Medetomidine is not an opioid, so naloxone (NARCAN®) will not reverse a purely medetomidine overdose. However, because medetomidine is always found in combination with opioids, including fentanyl, naloxone (NARCAN®) should still be administered whenever an opioid-involved overdose is suspected.

-

Research has not shown an association between medetomidine and skin wounds. Recent data from emergency department visits has shown that rates of substance use related skin and soft tissue infections (including wounds) fell to the lowest rate since Q1 2021 at the same time as the increase in medetomidine and the decrease in xylazine in the dope supply.

If you are experiencing substance use related wounds, many organizations in the Kensington area offer wound care and supplies. View locations and hours of operation.

Are you a medical provider looking for recommendations for treating substance use-associated wounds? Visit the trainings page for more information.

-

Yes. Medetomidine - associated withdrawal can cause racing heart, severe nausea and vomiting, excessive sweating, tremors, and confusion. Medetomidine - associated withdrawal can be much worse than withdrawal from drugs like opioids and xylazine and require emergency care.

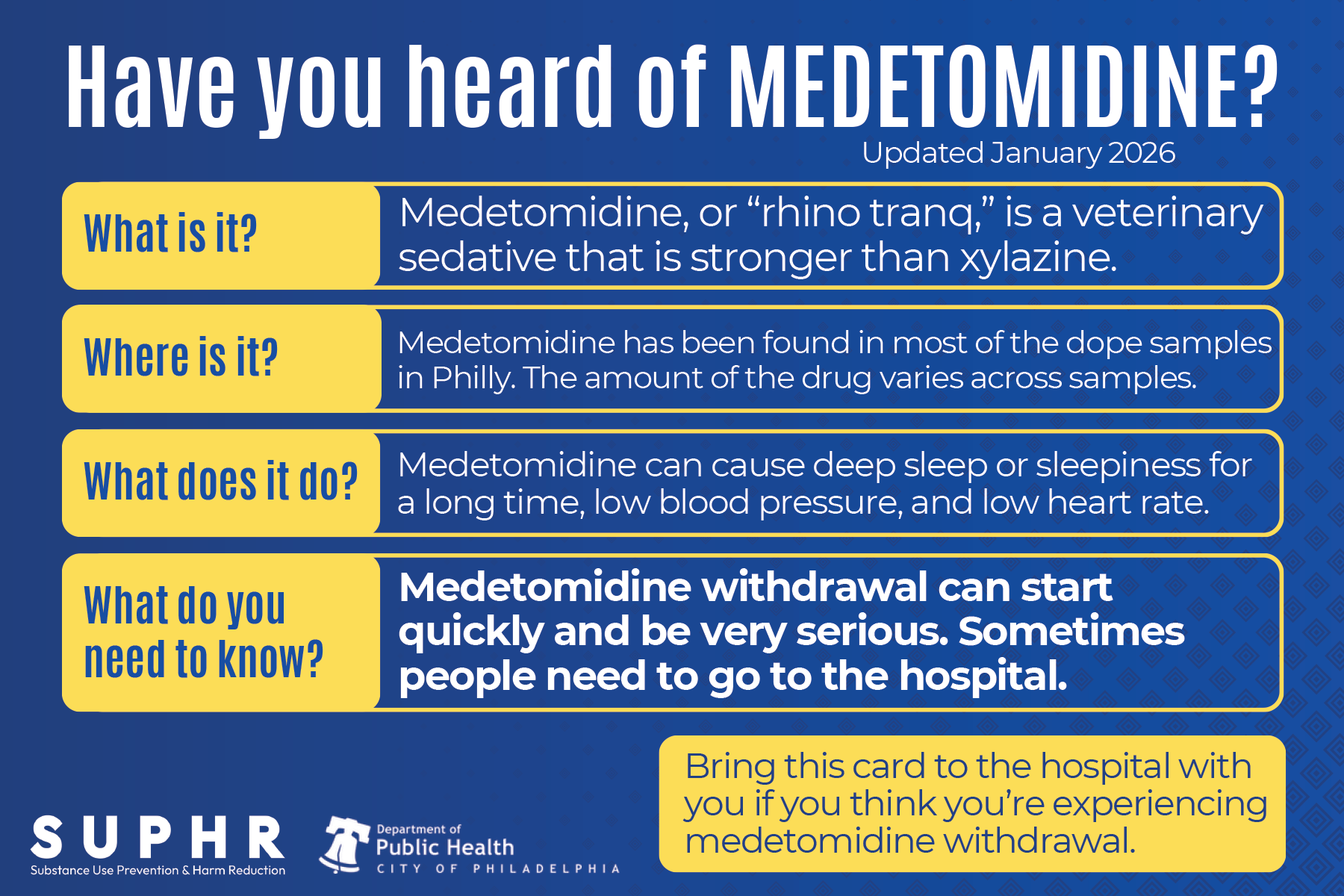

Medetomidine palm card

**Updated January 2026

Medetomidine, or “rhino tranq,” is a veterinary sedative that is stronger than xylazine.

Medetomidine has been found in most of the dope samples in Philly. The amount of the drug varies across samples.

Medetomidine can cause deep sleep or sleepiness for a long time, low blood pressure, and low heart rate.

Medetomidine withdrawal can start quickly and be very serious. Sometimes people need to go to the hospital.

Medetomidine withdrawal can cause:

a very fast heartbeat

very high blood pressure

going in and out of responding or being aware even while awake

heavy sweating

shaking or twitching

anxiety and restlessness

Signs to go to the hospital:

can’t stop throwing up

have chest pain

going in and out of responding or being aware, even while awake

otherwise experiencing more severe withdrawal symptoms than usual

Guidance for healthcare providers treating medetomidine withdrawal

Treating medetomidine withdrawal requires treating fentanyl withdrawal with long-acting opioid agonists like methadone and using adjunctive medications such as:

clonidine

guanfacine

tizanidine

dexmedetomidine

ketamine

olanzapine

hydroxyzine

benzodiazepines

prochlorperazine

chlorpromazine

Find current treatment guidance for medetomidine withdrawal from the Philadelphia Department of Public Health at: SubstanceUsePhilly.com/medetomidine

This card was created in June 2025. Check SubstanceUsePhilly.com for up-to-date treatment info.

Community alerts

Medetomidine withdrawal community alert - December 2024

Medetomidine community alert - May 2024

More resources

Medical and harm reduction responses to medetomidine are evolving. We will continue to update these resources and reports (last updated 1/27/2026).

Clinical guidelines

Medetomidine Inpatient Withdrawal Management: January 2026 Annals of Emergency Medicine article

Medetomidine Outpatient Withdrawal Guidelines: Developed by Dr. Michael Lynch at the University of Pittsburgh and shared with his permission.

Peer-reviewed papers

January 2026 Annals of Emergency Medicine article: Emergence of Medetomidine in the Illicit Drug Supply: Implications for Emergency Care and Withdrawal Management

Level of evidence: literature review/expert opinion

October 2025 Psychoactives article: Profound Opioid and Medetomidine Withdrawal: A Case Series and Narrative Review of Available Literature

Case series review describes several atypical withdrawal presentations, including extreme tachycardia and hypertension, tremors, anxiety, and protracted vomiting that were not effectively managed with conventional opioid withdrawal treatment protocols. Withdrawal was effectively managed with dexmedetomidine, given until patients could tolerate oral intake and swatches to another alpha2 agonist. Other medications and dosing protocols are described.

Level of evidence: case report

October 2025 American Journal of Emergency Medicine article: Assessing the Cardiac Safety of a Multimodal Protocol for ‘Tranq Dope’ Withdrawal: A Retrospective QTc Analysis

None of the following withdrawal protocol medications were associated with QTc prolongation: buprenorphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, olanzapine, droperidol, ketamine, guanfacine, tizanidine, diphenhydramine, lactated rings IV solution.

August 2025 Journal of Addiction Medicine article: Severe Fentanyl Withdrawal Associated with Medetomidine Adulteration: A Multicenter Study from Philadelphia, PA

In a cohort of 209 patients presenting to Philly-area emergency rooms with medetomidine withdrawal between Sept. 2024 and April 2025, 77.5% required ICU admission and 20% were intubated – lower proportions of patients than previous cohorts. Severe withdrawal complications, including encephalopathy and myocardial damage, were common, and seizures were overall uncommon.

In LC-MS/MS confirmatory toxicology, medetomidine metabolites were only detected in 65% of the cohort. Medetomidine may not always be detected in toxicology when patients present with severe withdrawal.

July 2025 International Journal of Molecular Sciences article: Biochemical Identification and Clinical Description of Medetomidine Exposure in People Who Use Fentanyl in Philadelphia, PA

Clinical phenotypes of sedative intoxication (sedation; bradycardia; and often hypotension) and withdrawal (tachycardia; hypertension and often encephalopathy) correlated with urinary medetomidine metabolites, but not xylazine.

Enzymatic pretreatment of samples was significant for accurate detection of medetomidine metabolites. Without pretreatment, the medetomidine metabolite 3-OH-M was detected in 100% of intoxicated samples and 68% of withdrawal samples. When glucuronidase pretreatment was performed, 3-OH-M was found in all intoxicated and withdrawal patients (100% in both groups), with significantly higher concentrations among intoxicated patients (8423 ng/mL vs. 34 ng/mL; p < 0.001). Glucuronidase pretreatment also increased detection of xylazine in samples.

May 2025 BioMed article: Decreased Effectiveness of a Novel Opioid Withdrawal Protocol Following the Emergence of Medetomidine as a Fentanyl Adulterant

Standard withdrawal treatment protocol initiated for patients in Philly-area emergency departments became less effective after the introduction of medetomidine into the city’s street opioid supply. Patients who came into emergency departments with withdrawal after August 2024, when Medetomidine became more common, had smaller reductions in Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS) scores and were admitted to the ICU at double the rate of patients who came in before. Patient-directed discharges also increased after the introduction of medetomidine.

Training

December 2025 Tennessee Harm Reduction Project ECHO: Medetomidine: Best Practices for a Changing Drug Supply

April 2025 Penn CAMP Webinar: An Emerging Adulterant in Philadelphia: Medetomidine Withdrawal in People Who Use Fentanyl

Reports and Health Advisories

June 2025 PDPH Health Alert Network (HAN) Update: Responding to overdose and withdrawal involving medetomidine

May 2025 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR): Notes from the Field: Suspected Medetomidine Withdrawal Syndrome Among Fentanyl-Exposed Patients — Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, September 2024–January 2025

May 2025 CDC MMWR: Notes from the Field: Severe Medetomidine Withdrawal Syndrome in Patients Using Illegally Manufactured Opioids — Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, October 2024–March 2025

May 2025 CDC MMWR: Overdoses Involving Medetomidine Mixed with Opioids — Chicago, Illinois, May 2024

April 2025 Medetomidine PDPH CHART: Changes in Philadelphia’s Drug Supply and Substance Use-Related Emergency Department Visits

December 2024 PDPH HAN Alert: Hospitals and behavioral health providers are reporting severe and worsening presentations of withdrawal among people who use drugs (PWUD) in Philadelphia

December 2024 Community Alert: Medetomidine is causing more severe withdrawal

May 2024 PDPH HAN Alert: In Philadelphia, medetomidine, a potent non-opioid veterinary sedative, has been detected in the illicit drug supply

May 2024 Community Alert: Medetomidine was found in Philly’s dope supply

This page is currently under development. Information regarding medetomidine, its effects, and treatment and harm reduction recommendations are still developing. Resources for community members, non-medical organizations, and healthcare providers will be available on this page as it becomes available. If you have any questions about information or material on this page, contact DPH.Opioid@phila.gov.